- Home

- Jayne Anne Phillips

Machine Dreams

Machine Dreams Read online

ACCLAIM FOR

Jayne Anne Phillips’s

MACHINE DREAMS

“A remarkable novelist debut and an enduring literary achievement.… Its subject is history and the passage of time—as mirrored in the fortunes of the Hampson family, whose own dissolution reflects the dislocations suffered by this country in the wake of the 1960s and Vietnam.… This astonishing book establishes Jayne Anne Phillips as a novelist of the first order.”

—Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“Reaches one’s deepest emotions. No number of books read or films seen can deaden one to the intimate act of art by which this wonderful young writer has penetrated the definitive experience of her generation.”

—Nadine Gordimer

“A story of conflict and love, of dreams put on perpetual hold, of losing faith with America but not with Americans … a book so deeply felt, so vividly imagined, that its characters seem not created at all but people breathing.… Machine Dreams shines with quiet eloquence … a rare and important work of fiction.”

—Newsday

“That Machine Dreams would be among the year’s best-written novels was easy to predict; that it is among the wisest of a generation’s attempts to grapple with a war that maimed us all is a stunning surprise.”

—The Village Voice Literary Supplement

“Astonishing and mysterious.… The fascination is in the telling.… Phillips expresses herself with clarity and grace: these lives matter.”

—Time

“Machine Dreams seems itself a thing in flight: gliding above the American landscape, illuminating a time and our own collective dream.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“A novel so brilliant it sticks in your head long after you have read it.… The compassion is so strong here that everyone is forgiven; Jayne Anne Phillips’ genius is to bring it home with such art and beauty and attention to detail that you can’t help but say ‘Wow! This is gorgeous!’ ”

—Los Angeles Times

“Lyrical … Machine Dreams is a plain American beauty.”

—Vogue

“An intensely American, beautifully written first novel. Southern voices … so true, and their experiences so fundamental to the hurly-burly of family life, that this novel is one of the finest in contemporary fiction.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“One’s first reaction to this novel is the general pleasure that fine writing affords; then, gradually, a deepening perception of the ironies of existence, communicated through the experiences of ordinary people; and finally there comes a lump in the throat and an almost palpable ache in the heart, in recognition of the vision of life that Phillips, with a fierce gentleness, lays bare.”

—Publishers Weekly

Jayne Anne Phillips

MACHINE DREAMS

Jayne Anne Phillips was born and raised in West Virginia. She is the author of two novels and two collections of stories. She is the recipient of the Sue Kaufman Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Bunting Institute fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships in fiction. Her work has been translated into fourteen languages.

ALSO BY

Jayne Anne Phillips

Shelter

Fast Lanes

Black Tickets

LIMITED EDITIONS

The Secret Country

How Mickey Made It

Counting

Sweethearts

FIRST VINTAGE CONTEMPORARIES EDITION, NOVEMBER 1999

Copyright © 1984 by Jayne Anne Phillips

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by E. P. Dutton, Inc., New York, in 1984.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Contemporaries and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments of permission to reprint previously published material will be found on this page.

The author wishes to express her thanks to The Ingram Merrill Foundation, The Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College, and The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown for support during the writing of this work. She also wishes to thank Rick Ducey, U.S. Army, Retired, and Geoffrey M. Boehm, helicopter pilot, First Cav., Vietnam, for their time and consideration.

Portions of this book have appeared in The Atlantic Monthly and in Grand Street. The Secret Country: Mitch was published as a limited edition by Palaemon Press, Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Phillips, Jayne Anne, 1952-

Machine dreams / Jayne Anne Phillips.

p. cm.

1. Family—West Virginia—History—20th century—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3566.H479M3 1999

813′.54—dc21 99-18315

eISBN: 978-0-307-80884-4

Author photograph © Marion Ettlinger

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

for my family,

past and present

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Reminiscence To A Daughter: Jean

The Secret Country: Mitch

War Letters: Mitch, 1942–45

Machine Dreams: Mitch, 1946

Anniversary Song: Jean, 1948

Coral Sea: Mitch, 1950

The House At Night: Danner, 1956

Machine Dreams: Billy, 1957

Reminiscence To A Daughter: Jean, 1962

Radio Parade: Danner, 1963

The Air Show: Billy, 1963

Amazing Grace: Danner, 1965

Moonship: Danner, 1969

November And December: Billy, 1969

War Letters: Billy, 1970

The World: Danner, 1972

Machine Dream: Danner

Permissions Acknowledgments

“Here is the story of flying, from the dreams of ancient Greece to the wonders of the present day, presented in brief, authoritative text and superb watercolor paintings. It is a fascinating story of people and ideas, of adventure and daring, and of flying machines.”

—MELVIN B. ZISFEIN,

Flight, A Panorama of Aviation

“The Greeks believed that their heroic dead appeared before the living in the form of a horse.… The soul of the deceased was often depicted in horse-shape.”

—NIKOLAS YALOURIS,

Pegasus: The Art of the Legend

“Now he (Pegasus) flew away and left the earth, the mother of flocks, and came to the deathless gods: and he dwells in the house of Zeus and brings to wise Zeus the thunder and lightning.”

—HESIOD,

The Theogony, vv. 284–86

“And the voice said:

Well you don’t know me,

but I know you

And I’ve got a message to give to you.

Here come the planes

So you better get ready. Ready to go. You can come

as you are, but pay as you go …

They’re American planes. Made in America.

Smoking or non-smoking?”

—LAURIE ANDERSON

“O Superman”

REMINISCENCE TO A DAUGHTER

Jean

It’s strange what you don’t forget. We had a neighbor called Mrs. Thomas. I remember reaching up a long way to pull the heavy telephone—a box phone with a speaking horn on a cord—onto

the floor with me. Telephone numbers were two digits then. I called 7, 0, and said, “Tommie, I’m sick. I want you to come over.” I can still hear that child’s voice, with the feeling it’s coming from inside me, just as clearly, just as surely as you’re standing there. I was three years old. I saw my hands on the phone box, and my shoes, and the scratchy brown fabric of the dress I was wearing. I wasn’t very strong and had pneumonia twice by the time I was five. Mother had lost the child before me to diphtheria and whooping cough, and stillborn twins before him. She kept me dressed in layers of woolens all winter, leggings and undershirts. She soaked clean rags in goose grease and made me wear them around my neck. Tommie would help her and they’d melt down the grease in a big black pot, throw in the rags, and stir them with a stick while I sat waiting, bundled in blankets. They lay the rags on the sill to cool, then wrapped me up while the fumes were still so strong our eyes teared. I stood between the two women as they worked over me, their hands big and quick, and saw nothing but their broad dark skirts.

I was so skinny as a kid, and had such big brown eyes. In the summer I was black as a darkie and Mother called me her pickaninny. She used to say I was the ugliest baby she ever saw; when I was a few days old she lay me in the middle of the high walnut bed and stood looking. The neighbor woman at her elbow said, “Just you wait. She’ll be the joy of your life.” Mother would tell that story as I was growing up—I don’t know how many times I heard it—then she’d smile at me and say, “And it’s true, you are.”

Later you look back and see one thing foretold by another. But when you’re young, those connections are secrets; everything you know is secret from yourself. I always assumed I’d have my own daughter. I picked out your name when I was twelve, and saved it. In a funny way, you were already real. I never felt that way about your brother. You were first-born; then he arrived and made a place for himself; I’d had no ideas about him. Maybe it’s that way with boy children; maybe they’re luckier.

I was like an only child, growing up alone with my mother. She’d lost those three babies before me, and my brother and sister who survived were ten and twelve years older—out of the house by the time I needed someone to talk to. They had grown up very differently—Dad had money then. Mother’s furniture was new; the house was kept up; the street, with all those big trees shading the sidewalk, was referred to as Quality Hill. Dad had the biggest lumber business in the state at one time. He was twenty-five years older than Mother and she was his second wife; at the time they married, he had grown children nearly her age. Even though he was rich, her parents hadn’t wanted her to go with him—I guess he had quite a reputation: an eccentric, a womanizer. Her family ran a small hotel in Pickens. That town is a ghost town now but the building, the old hotel, is still standing. Did I ever take you to see it? He stayed there on business trips and Mother had seen him come and go. One night she was clerking at the check-out desk and he suddenly noticed her. She was seventeen; he must have seemed worldly and dashing. After a few months of courtship and presents—mostly by mail—they eloped and went to Niagara Falls for a wedding trip. It was her first time away from home since childhood; all her clothes were new and they stayed in a suite of grand rooms. Mother told me how she’d sit up at night, writing letters back about the steamer boat and the spray of the Falls; how the spray turned colors in the sun but was cold even in summer and smelled to her of mint or violets. She begged her mother to forgive her, but the letters weren’t answered; it was a year before they’d let her come visit.

Dad brought her home through Hampton to impress her. Now it’s just shacks bought out by the mines and fallen to ruin, but then it was a town of forty frame saltboxes he’d built by the river to house his workers. The mill hands lined the tracks and cheered as the train pulled in.

They lived there near the mill in the master house for the first couple of years. She was a help to him in the business, though he never admitted as much and pretended not to take her advice. Soon he moved her to the big house in town and was home every other night; he was accustomed to doing just as he liked and had a succession of “secretaries” out at the mill. My sister told me she remembered a big row between them when she was thirteen or so. I was just a baby. He’d hired a manager that summer and was going to be in town most of the time; he said there was a lot of work to do and he was going to move his secretary into one of the spare rooms down the hall from his. Mother said she’d sooner march down the street naked than take one of his women under her own roof. He said by God it was his roof, he’d paid for every inch of it. He did move the girl in for a few weeks—daughter of one of the mill workers. She wasn’t very bright and Mother ended up being nice to her, but my sister hated Dad from that time on and never spoke to him again except when threatened. But what toys she had as a child! China dolls and a dollhouse with a circular staircase. I think of those times as grand because they had no money worries, but Dad was always hard to live with. Still, he was a shiny figure, dapper, and gone from home enough that they were often left in peace.

By the time I was seven the mill was lost and he was a terror, sentimental or raging. He’d always been a drinker but he drank more; he’d extended credit to Easterners and what we called Gypsies—Italians from the upstate river towns. He liked being owed and flattered, begged for more time. He thought he was doing good works by letting his buyers go further and further into debt, and the Depression finished him.

We got along, but just barely. Mother had kept every stitch my elder sister hadn’t worn out, and she made those clothes over to fit me. My dresses were always mismatched affairs of good fabrics, twelve years out of style. I liked them and thought I looked grown-up. We kept a big garden and canned for weeks—she had a full pantry and those cloudy jars fed us through the winter. Any money we had came from the sale of milk or cream or butter—we had four cows in the barn, up the hill back of the house. Mother did the work year-round but I remember the cows especially in summer. We seemed to spend the long days in attendance to them while Dad sat on the porch or disappeared into the unused room on the stifling third floor of the house. He was totally unpredictable and talked to himself. Sometimes he fed the cows or walked out in the evening to inspect the barn, to knock on the falling boards with his fist and listen as though testing the wood. But he did chores as a whim. Usually I fed the cows and chickens. It used to occur to me at the age of seven and eight how stupid those cows were—like big warm rocks. Though we came to the barn every day at regular times, they didn’t recognize us except as they’d recognize rain or snow. They didn’t even have the nervousness and greed of the chickens, but ate placidly, like machines. The only time they seemed at all human was at calving, and that was terrible to watch. They bawled in pain and seemed bewildered, as though they didn’t know what hurt them. Then the calf was out on the straw, blinking.

Mother milked into a quart cup and dumped the milk in a can. When the can was full she pulled it to the house in a hand wagon. We had the coolest cellar, like a still tomb, with stone walls and a stone floor. Rough shelves along the side were lined with mason jars sealed full of tomatoes and beans and beets. The jars were just jars but you were always aware of them in the dimness, dense and weighted. The milk crocks were on the floor, white earthen urns. Mother wore a long man’s apron over her dress and skimmed the cream off the milk with a wooden spoon shaped like a small flat spade. We dipped the milk back into cans with a gourd dipper and carried them up the stone steps, across the yard into the kitchen. The bottles had to be boiled and the milk strained through a sterile cloth. She set some of it aside and let it curdle to frothy clumps the size of popcorn, then poured that heavy yellow cream over it and ground fresh pepper on top. Her cheese was famous but I wouldn’t touch it, and they had to beg me to drink milk. I guess I didn’t like it because we were always fooling with it, from dawn to dusk, the cows and the milk and the bottles.

Mr. Hardesty delivered for us and I helped him in the summer. I could see him driving the cart along from way

down the street. He had an old barrel-chested workhorse named Gus, and that horse knew every stop by heart. Gus was well known around town. Mr. Hardesty did landscaping and plowing as well—Gus wore blinders then and pulled a big double rake by harness; they graded yards for seeding or turned gardens. When we delivered milk, I met them at the top of the hill and handed up our four metal racks of four bottles each. Then I rode beside Hardesty and jumped down to take the orders to the doorsteps. The horse always waited just long enough. There was one customer who’d died a couple of years before I’d ever started helping, but Gus stopped at that house anyway. We sat waiting the time it would have taken me to run to the door and back.

My father got worse as time went on. When my friends stayed with me, he used to stride into the room, pull the sheets off us, and tell them to get dressed—he didn’t want strangers in his house at night. One autumn we were burning trash on the hill. He picked up a pitchfork of blazing leaves and chased Mother around the fire. After that we had to have him put away. A couple of weeks later, a guard knocked him down and that was all. I was fourteen. My mother and I turned on every light in the house that evening and sat on the porch, looking at the street. October, a clean moisture in the air. We both felt such relief. We’d been ashamed to send him there, but we’d gotten afraid of him and had no money for anything better. I didn’t know until he was gone what a shadow he’d cast. Partly because we were free of him, the next few years were good. We took in roomers, students from the college. I had a part-time job and lots of friends; I was eager to know people. You may not like me to say so, but high school was the best time of my life.

On Sundays in the spring, the kids in my crowd got all dressed up and walked downtown to the drugstore for sodas—that was our big thrill. But Tomblyn’s was beautiful then—as grand, everyone said, as any soda fountain in Washington or New York. The big mirror was beveled glass, and the fountains themselves were brass. The floor was marble tiles with a black border, and the deep booths, mahogany. Only the high carved ceiling and bar wall are left now, and the store is half as large as it was.

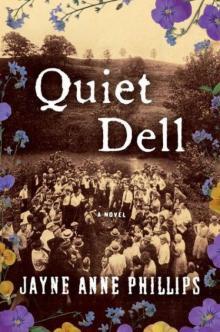

Quiet Dell: A Novel

Quiet Dell: A Novel Lark and Termite

Lark and Termite Machine Dreams

Machine Dreams Fast Lanes

Fast Lanes Black Tickets

Black Tickets