- Home

- Jayne Anne Phillips

Black Tickets

Black Tickets Read online

Acclaim for Jayne Anne Phillips’s

BLACK TICKETS

“Extraordinary.… Phillips is a wonderful writer, concerned with every sentence and seemingly always operating out of instincts that are visceral and true—perceived and observed originally, not imitated or fashionably learned.… Phillips shines brightly.… This is a sweetheart of a book.”

—John Irving, The New York Times Book Review

“The unmistakable work of early genius trying her range, a dazzling virtuoso range that is distinctly her own. Jayne Anne Phillips is ‘the real thing.’ ”

—Tillie Olsen

“Remarkable.… Hers is an authentic and original voice.… [Black Tickets is] just cause for celebration.”

—Newsweek

“Phillips writes a knockout prose. Hold on to your seats!”

—Annie Dillard

“Black Tickets is the work of authentic genius.… Phillips … is indeed an awesome talent.… From the first sentence of the book … her prose has you in its thrall. It is precise, tough, glistening with images.… You want to read every word.… Her writing has an astonishingly tactile quality. You do not read her stories. You feel, hear, see them.… The range of stories here is impressive.”

—Newsday

“Phillips’s prose is audacious, musical, and fresh. She is unafraid, and seems almost possessed by the American language. Her work has depth, and power, and I admire it enormously.”

—Frank Conroy

“Her writing burns a white heat, deriving intensity from the most everyday situations as easily and expertly as from glaring exotica.… She makes even the most public acts intimate.”

—Atlanta Constitution

“Phillips casts a brilliant, fluorescent light.… She is pitiless. She is gifted. She must be read.”

—Robie Macauley

“[A] virtuoso collection.… Phillips’s use of language is richly sensuous. She takes street slang all the way to poetry and back, hovering on the edge of surrealism but … always sustaining a lucid narrative flow.… Dazzling dramatic monologues … the sheer range of subject matter, and the lively cast of characters … drawn from all the nooks and crannies of American urban and country life, declare the tireless researcher as well as the exuberant stylist in Ms. Phillips.… She has the power to bring us to the quick of physical sensation. She can write both with supreme simplicity and with metaphorical bravura.… These stories have, of course, their forerunners and ‘influences’—Joyce, Steinbeck, and Plath.… But they also possess a freshness and intensity entirely their own. Few enough writers at any time have the power to take language and polish it until it is sharp and gleaming again. Phillips is one of them.”

—The Times Literary Supplement

“These are wonderful stories. Jayne Anne Phillips displays energy, artistic poise, and electric talent.”

—Tim O’Brien

“Phillips’s writing hangs together, like the monologue of a rapt seer, random bits of the world fused together in the self-willed power of her vision.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“Phillips is an awesome talent.… She writes as though possessed.”

—The Indianapolis Star

“This woman is part witch, all poet, and a fabricator of passionately told stories.”

—Frederick Busch

“Phillips explores mercilessly the human condition, attempting material few other writers have dared. Even fewer have succeeded as she does in conveying the raw emotional content of their themes while … transforming it with a poet’s vision.”

—The Plain Dealer

“Jayne Anne Phillips is a stunning writer. She tells about the pains and pleasures of being a woman with surgical honesty and a tenderness that touches the heart.”

—John Leggett

“Phillips wonderfully catches the tones and gestures in which familial love unexpectedly persists even after altered circumstances have made it impossible to express directly, and the ways in which grown children, while cherishing even an unrewarding freedom, can be caught and hurt and consoled by their vestigial yearning for dependence, safety, a human closeness that usually seems forever lost.”

—The New York Review of Books

Jayne Anne Phillips

BLACK TICKETS

Jayne Anne Phillips was born and raised in West Virginia. She is the author of one other collection of widely anthologized stories, Fast Lanes, and three novels, MotherKind, Shelter, and Machine Dreams. She has won the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction and an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, a Bunting Institute fellowship, a Guggenheim fellowship, and two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships in fiction. Her work has been translated into twelve languages.

ALSO BY

Jayne Anne Phillips

MotherKind

Shelter

Fast Lanes

Machine Dreams

LIMITED EDITIONS

The Secret Country

How Mickey Made It

Counting

Sweethearts

FIRST VINTAGE CONTEMPORARIES EDITION, SEPTEMBER 2001

Copyright © 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979 by Jayne Anne Phillips

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Delacorte Press/Seymour Lawrence Books, New York, in 1979.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Contemporaries and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The author would like to thank the National Endowment for the Arts and the Corporation of Yaddo for their assistance.

Some of the stories in this book first appeared in the following publications: “Wedding Picture” in New Letters; “Home” in The Iowa Review; “Sweethearts” and “Under the Boardwalk” in Truck Magazine; “Lechery” in Persea; “Gemcrack” and “El Paso” in Ploughshares; “1934” in Canto; “Solo Dance” in North American Review; “The Heavenly Animal” in Fiction International; “Happy” in Paris Review; “Souvenir” in Redbook; “Slave” in Loka 2; “Cheers” in Attaboy; “Snow” in Fiction; “Country” (as “Easy”) in Big Deal IV; “Blind Girls,” “The Powder of the Angels, and I’m Yours,” “Stripper,” “Strangers in the Night,” “What It Takes to Keep a Young Girl Alive,” “Satisfaction,” and “Accidents” in Sweethearts; “Sweethearts,” “Under the Boardwalk,” and “Blind Girls” appeared in Pushcart Prize II, Best of the Small Presses; “Home” and “Lechery” appeared in Pushcart Prize IV, Best of the Small Presses.

Lyrics from “Some Enchanted Evening” by Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein II: Copyright © 1949 by Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein II. Copyright Renewed. Williamson Music, Inc., owner of publication and allied rights. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission. Lyrics from “Ball and Chain” by “Big Momma” Thornton: Bay Tone Music Publishers and Criesteval Music. Used by permission. Lyrics from “Under the Boardwalk” by Arties Resnick and Kenny Young: Copyright © 1964 by The Hudson Bay Music Company. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Lyrics from “A Summer Place” by Max Steiner & Mack Discant: © 1964 Warner Bros., Inc. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Phillips, Jayne Anne, 1952–

Black tickets / Jayne Anne Phillips.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-80881-3

1. United States—Social life and customs—20th century—Fiction. 2. Man-woman relationships—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3566.H479 B58 20

01

813′.54—dc21 2001026079

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

Our souls were clean,

but the grass didn’t grow.

—Van Morrison

“Streets of Arklow”

from Veedon Fleece

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Wedding Picture

Home

Blind Girls

Lechery

Mamasita

Black Tickets

The Powder of the Angels, and I’m Yours

Stripper

El Paso

Under the Boardwalk

Sweethearts

1934

Solo Dance

The Heavenly Animal

Happy

Stars

The Patron

Strangers in the Night

Souvenir

What It Takes to Keep a Young Girl Alive

Cheers

Snow

Satisfaction

Country

Slave

Accidents

Gemcrack

Characters and voices in these stories began in what is real, but became, in fact, dreams. They bear no relation to living persons, except that love or loss lends a reality to what is imagined.

Wedding Picture

MY MOTHER’S ANKLES curve from the hem of a white suit as if the bones were water. Under the cloth her body in its olive skin unfolds. The black hair, the porcelain neck, the red mouth that barely shows its teeth. My mother’s eyes are round and wide as a light behind her skin burns them to coals. Her heart makes a sound that no one hears. The sound says each fetus floats, an island in the womb.

My father stands beside her in his brown suit and two-tone shoes. He stands also by the plane in New Guinea in 1944. On its side there is a girl on a swing wearing spike heels and short shorts. Her breasts balloon; the sky opens inside them. Yellow hair smooth as a cat’s, she is swinging out to him. He glimmers, blinded by the light. Now his big fingers curl inward. He is trying to hold something.

In her hands the snowy Bible hums, nuns swarming a honeyed cell. The husband is an afterthought. Five years since the high school lover crumpled on the bathroom floor, his sweet heart raw. She’s twenty-three, her mother’s sick, it’s time. My father’s heart pounds, a bell in a wrestler’s chest. He is almost forty and the lilies are trumpeting. Rising from his shoulders, the cross grows pale and loses its arms in their heads.

Home

I’M AFRAID Walter Cronkite has had it, says Mom. Roger Mudd always does the news now—how would you like to have a name like that? Walter used to do the conventions and a football game now and then. I mean he would sort of appear, on the sidelines. Didn’t he? But you never see him anymore. Lord. Something is going on.

Mom, I say. Maybe he’s just resting. He must have made a lot of money by now. Maybe he’s tired of talking about elections and mine disasters and the collapse of the franc. Maybe he’s in love with a young girl.

He’s not the type, says my mother. You can tell that much. No, she says, I’m afraid it’s cancer.

My mother has her suspicions. She ponders. I have been home with her for two months. I ran out of money and I wasn’t in love, so I have come home to my mother. She is an educational administrator. All winter long after work she watches television and knits afghans.

Come home, she said. Save money.

I can’t possibly do it, I said. Jesus, I’m twenty-three years old.

Don’t be silly, she said. And don’t use profanity.

She arranged a job for me in the school system. All day, I tutor children in remedial reading. Sometimes I am so discouraged that I lie on the couch all evening and watch television with her. The shows are all alike. Their laugh tracks are conspicuously similar; I think I recognize a repetition of certain professional laughters. This laughter marks off the half hours.

Finally I make a rule: I won’t watch television at night. I will watch only the news, which ends at 7:30. Then I will go to my room and do God knows what. But I feel sad that she sits there alone, knitting by the lamp. She seldom looks up.

Why don’t you ever read anything? I ask.

I do, she says. I read books in my field. I read all day at work, writing those damn proposals. When I come home I want to relax.

Then let’s go to the movies.

I don’t want to go to the movies. Why should I pay money to be upset or frightened?

But feeling something can teach you. Don’t you want to learn anything?

I’m learning all the time, she says.

She keeps knitting. She folds yarn the color of cream, the color of snow. She works it with her long blue needles, piercing, returning, winding. Yarn cascades from her hands in long panels. A pattern appears and disappears. She stops and counts; so many stitches across, so many down. Yes, she is on the right track.

Occasionally I offer to buy my mother a subscription to something mildly informative: Ms., Rolling Stone, Scientific American.

I don’t want to read that stuff, she says. Just save your money. Did you hear Cronkite last night? Everyone’s going to need all they can get.

Often, I need to look at my mother’s old photographs. I see her sitting in knee-high grass with a white gardenia in her hair. I see her dressed up as the groom in a mock wedding at a sorority party, her black hair pulled back tight. I see her formally posed in her cadet nurse’s uniform. The photographer has painted her lashes too lushly, too long; but her deep red mouth is correct.

The war ended too soon. She didn’t finish her training. She came home to nurse only her mother and to meet my father at a dance. She married him in two weeks. It took twenty years to divorce him.

When we traveled to a neighboring town to buy my high school clothes, my mother and I would pass a certain road that turned off the highway and wound to a place I never saw.

There it is, my mother would say. The road to Wonder Bar. That’s where I met my Waterloo. I walked in and he said, ‘There she is. I’m going to marry that girl.’ Ha. He sure saw me coming.

Well, I asked, Why did you marry him?

He was older, she said. He had a job and a car. And Mother was so sick.

My mother doesn’t forget her mother.

Never one bedsore, she says. I turned her every fifteen minutes. I kept her skin soft and kept her clean, even to the end.

I imagine my mother at twenty-three; her black hair, her dark eyes, her olive skin and that red lipstick. She is growing lines of tension in her mouth. Her teeth press into her lower lip as she lifts the woman in the bed. The woman weighs no more than a child. She has a smell. My mother fights it continually; bathing her, changing her sheets, carrying her to the bathroom so the smell can be contained and flushed away. My mother will try to protect them both. At night she sleeps in the room on a cot. She struggles awake feeling something press down on her and suck her breath: the smell. When my grandmother can no longer move, my mother fights it alone.

I did all I could, she sighs. And I was glad to do it. I’m glad I don’t have to feel guilty.

No one has to feel guilty, I tell her.

And why not? says my mother. There’s nothing wrong with guilt. If you are guilty, you should feel guilty.

My mother has often told me that I will be sorry when she is gone.

I think. And read alone at night in my room. I read those books I never read, the old classics, and detective stories. I can get them in the library here. There is only one bookstore; it sells mostly newspapers and True Confessions oracles. At Kroger’s by the checkout counter I buy a few paperbacks, bestsellers, but they are usually bad.

The television drones on downstairs.

I wonder about Walter Cronkite.

When was the last time I saw him? It’s true his face was pouchy, his hair th

inning. Perhaps he is only cutting it shorter. But he had that look about the eyes—

He was there when they stepped on the moon. He forgot he was on the air and he shouted, ‘There … there … now—We have Contact!’ Contact. For those who tuned in late, for the periodic watchers, he repeated: ‘One small step …’

I was in high school and he was there with the body count. But he said it in such a way that you knew he wanted the war to end. He looked directly at you and said the numbers quietly. Shame, yes, but sorrowful patience, as if all things had passed before his eyes. And he understood that here at home, as well as in starving India, we would pass our next lives as meager cows.

My mother gets Reader’s Digest. I come home from work, have a cup of coffee, and read it. I keep it beside my bed. I read it when I am too tired to read anything else. I read about Joe’s kidney and Humor in Uniform. Always, there are human interest stories in which someone survives an ordeal of primal terror. Tonight it is Grizzly! Two teen-agers camping in the mountains are attacked by a bear. Sharon is dragged over a mile, unconscious. She is a good student loved by her parents, an honest girl loved by her boyfriend. Perhaps she is not a virgin; but in her heart, she is virginal. And she lies now in the furred arms of a beast. The grizzly drags her quietly, quietly. He will care for her all the days of his life … Sharon, his rose.

But alas. Already, rescuers have organized. Mercifully, her boyfriend is not among them. He is sleeping en route to the nearest hospital; his broken legs have excused him. In a few days, Sharon will bring him his food on a tray. She is spared. She is not demure. He gazes on her face, untouched but for a long thin scar near her mouth. Sharon says she remembers nothing of the bear. She only knows the tent was ripped open, that its heavy canvas fell across her face.

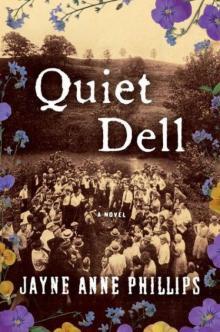

Quiet Dell: A Novel

Quiet Dell: A Novel Lark and Termite

Lark and Termite Machine Dreams

Machine Dreams Fast Lanes

Fast Lanes Black Tickets

Black Tickets