- Home

- Jayne Anne Phillips

Fast Lanes Page 12

Fast Lanes Read online

Page 12

The girls’ gym facilities were identical to the boys’, only smaller and painted less often. The lockers were older, battered and olive green, their catches and undependable locks installed thirty years ago. The rooms themselves were thick-walled, always damp to the touch. Painted dark green to shoulder height, they took on the pale color of the ceiling, a sour yellow reminiscent of sickness. Slanted cement floors drained into metal drains. Along the walls were the green benches where girls had sat to pull on their stockings in the forties and fifties; now we wore bright wool knee socks to match our sweaters, or fuchsia tights. The room was long and narrow, barely lit by ceiling bulbs and basement windows of dappled, frosted glass, barred with black iron. We liked to put on our skirted, dark blue gym suits and refer to ourselves as maniacs: pretense of snarls and drools as we bent to lace our tennis shoes. Empty now, the space resembled a neglected dungeon.

I walked naked into the shower room, a narrow cul-de-sac that smelled of mildew. The lights were badly wired and flickered. Incongruously beautiful, the shower stalls were floor-to-ceiling marble slabs, the marble a pearl white veined with gray. Their heavy doors banged, the dark paint peeling. One long horizontal mirror faced the showers over small sinks; the mirror was always cloudy, sweating, flecks of the glass gone so the surface seemed pocked with minute brown snowflakes. At the end under the windows were two toilets in wooden stalls. On their green doors someone had scratched with a nail file long ago: “No shits during showers.” Just above this communication hung a more recent, official note printed by hand: DO NOT FLUSH TOILETS WHILE SHOWERS ARE RUNNING. To the right of the sign, another scrawled message: “Piss in the shower, Shit elsewhere, Good luck.”

Just as I got inside and the water gurgled, bursting violently down in a hard spray, the yellow light dimmed and went out. I heard Kato come into the room, saying my name, feeling her way along the shower doors.

“Danner,” she said, “is that you?”

“Yes,” I answered. “Why are you still here?”

“I had to take the art supplies back upstairs.”

“Kato, what happened to the light?” I reached to latch the door and touched instead Kato’s cold stomach as she stepped inside.

“The bulb must be out again. Oh, make it warmer, I’m freezing.”

“This is my shower,” I said, “it’s warm enough.”

She shoved me as though in play directly under the hard warm spray and boxed her fists gently against my hands. I turned away and she moved to stand close behind me. I felt the long cool length of her body. She was laughing, and tense; she put her hands lightly on my waist and hummed a bar of “Blue Moon,” then faked an openmouthed vampire kiss on my shoulder.

“You smell like Billy, do you know that?” She sighed, her voice slowed and changed. “You and Billy smell the same.”

I said nothing.

“Billy’s going away, isn’t he? He’s told you, I know he has.”

“I don’t know, Kato. Maybe he will.”

“Shit,” she whispered, like a plea, and her voice broke. She put her arms around me from behind and leaned into me with all her weight as though holding on for support.

“Kato—”

She was crying. “But he can’t go. You have to tell him.”

“Let go, OK?” In the warm water and the dark, I smelled the flowery musk of her wet hair. I stood still and she held on to me, swaying; I felt her face on the back of my neck, moving back and forth like the face of someone struggling in a dream. Over the running of the water I heard her ragged sobs, long sounds partially breathless, gasping. I twisted to face her and she let me but wouldn’t let go. I could barely see her clenched face and I was frightened.

“Kato, please, calm down. Take a deep breath, try to breathe.”

She held me, sliding down, her face on my stomach, my thighs, until she slid to her knees on the wet cement and crouched at my feet. The lights flickered then, on, off, on. I knelt beside her and she looked up at me, not really seeing me.

“Oh, God,” she said, “no one will help me.” She covered her face with her hands.

“I will, Kato, I will if I can. Stay here, I’ll get some towels. Stay right here.”

I only left her for a minute while I looked through the lockers for dry towels. When I came back she was standing in front of the mirror, the shower still running behind her. Someone had left a matte knife on the sink. Kato had the knife in her hand and she held one arm straight over her head. She watched herself in the mirror and traced a long ragged cut from her wrist to her armpit. She did it incredibly fast, with no expression, as though what she saw in the glass bore no connection to her. The little knife dropped into the sink as I reached her and she turned to me, her face stony, blood rising along the cut and pooling in the cup of her hand.

“You did the wrong thing,” Billy said.

“Look, I couldn’t tell then that it wasn’t so bad. She was bleeding, I couldn’t tell.”

“You should have helped her get her clothes on and come and found me.”

“Billy, if the cut had been deeper she could have bled to death while I was looking for you.”

“But it wasn’t so deep.” Above him, Jean’s kitchen clock ticked like a mechanical heartbeat. Finally, it was dark and the day was over. Billy shook his head. “Did she mean it to be worse?”

“I don’t know. The knife was dull and she couldn’t press hard, the way she held her arm. But she cut herself. She had thirty stitches. When I found you, Billy, what would you have done? Sewn up her arm? Oh, you have to let other people help now.”

He didn’t answer, his hands flat on the surface of the oak table. They hadn’t let him see her at the hospital, but later, when she went home with her father, he’d been there, waiting, for hours.

“Billy, what did she say to you?”

“She was in her room, lying down. She made light of it, said they gave her free Valium, and she’s going to visit her aunt in Ohio. She said Dayton wasn’t New York City but it’s bigger than Bellington.” His voice dropped. “She said she was sorry.”

“Did you talk to Shinner?”

Billy nodded. “He said not to stay because of Kato, that she’d be with his sister until Christmas, maybe the whole school year. That we could write and talk but there should be distance.”

“Billy,” I said, “maybe he’s right.”

He looked, bewildered, into the air, his eyes wet. “I told her I was just going down to look. That’s all, take a look.”

The gymnastics show occurred on schedule, two days later, on a cold Friday night. Kato had been sent to Ohio to her relatives and Billy had canceled his performance on the trampoline. I went to the show only because I couldn’t face staying home with Jean and Mitch, and Billy in his room in silence, his suitcase packed. My father drove me to the school and I walked through various routines with my classes, but toward the end I couldn’t face the last number, the candling maneuvers to “Blue Moon” in darkness. I didn’t want to see a hundred girls moving flames in patterns, shadows passing over the homemade moon.

I made my way outside and stood by the big double doors of the school. Boys from the country stood out there—the ones who wore boots and hunting caps with earflaps, and torn, fleece-lined leather jackets. One of them offered me a cigarette. We stood, smoking, and I watched them. What made sense? This moment was real. In some other instance these four boys might sneer at me, as they often sneered, threateningly, at girls from town. Or they might attack me. Why was the world one thing and not another?

I stood breathing the cold air, smelling the stark, clean cold. The boys jostled each other, drinking from a flask, and filed slowly out into the dark. They walked toward a pickup truck parked in the high school lot, where they could drink without fear of discovery. I watched them go and looked into the darkness in front of me, into the circular, empty drive of the school and the highway beyond.

A man walked unsteadily toward me out of the snow.

I wasn’t af

raid of him; I felt a solidarity with all outcasts. I wasn’t supposed to have to wrap bleeding girls in towels, or walk us both half naked into a school hallway for help. I wasn’t supposed to smoke cigarettes with country boys, or smoke cigarettes in the light where anyone could see, or even stand in the snow in a skimpy gym suit, shivering. Besides, I recognized the man by his thick, broad shoulders, and the set of his body. He came nearer and stopped opposite me. It was Kato’s father.

Shinner Black weaved slightly in the dark. He stood with legs spread and might have sunk slowly into one of the graceful gymnast’s splits I’d seen inside. “I knew your mother in high school,” he said to me.

I moved a little, stepping back toward the shelter of the building. “Maybe you’d better stand against this wall here,” I said.

He brought his feet together, straightened, and walked two steps closer. “Did you hear me?” he asked softly.

His voice was melodic. Despite the haze of his drunkenness, he seemed informed by some wonder and looked carefully at me. Now he stood in the light as the snow fell behind him, and I saw in his face the smooth, shadowed face of the boy in my mother’s scrapbook photographs. He sensed my surprise and my apprehension; his light eyes were unfocused but oddly alert, the eyes of a person hypnotized rather than blearily drunk. He searched my face with his distant gaze, as though looking for another face beneath my features.

“I was Tom Harwin’s best friend,” he said. “After that summer, I joined the army.” He stared off into the weather, then jerked his head as if something had occurred to him. “You know who I mean? Tom. Your mother’s beau, Tom and Jean.”

“Yes, I know.”

He came suddenly close, bent forward as though he were falling. Reflexively, I put my hands up to stop him. He leaned heavily against me at arm’s length, his chest against the palms of my hands. His coat was open. I felt the warmth of his skin through the thin fabric of his shirt, and the vibrations of his voice.

“You should have seen this town then,” he said, looking at the ground. “We had a good time the year before he died. Everyone was gone to the war. We high school boys, we were the men of the town.”

To keep my own balance, I had to lean slightly toward him. “Mr. Black,” I said. Across the parking lot, I saw the boys pause in the passing of their flask and stand watching us.

“I found out better,” Shinner Black said. “In the war, in France, nobody even spoke English. That was a joke we had.”

I waited, then he smiled and seemed to regain his balance. He stood, his face inches from mine, and put his hands on my shoulders. He held me so tightly I felt the pressure of each of his fingers. “People can’t live in this world,” he said. His voice was furious and tender; I felt the supportive, viselike grip of his hands and an unfamiliar, charged dizziness. The pressure of his grasp seemed to lift me toward him and I didn’t resist. I moved my hands in confusion and inadvertently touched his warm throat. We stood totally alone in the snow, and the space in which we stood seemed to turn in unhurried, resolute circles. What remained outside—the walls of the building behind us, the white ground and the highway, the parking lot and the boys, who yelled Shinner’s name once, twice—blurred and receded. Shinner’s hands relaxed their hard grip and he still held me, near him. We stood motionless.

I must have looked terrified. The boys had begun walking toward us; when they were close enough to see my face, they broke into a loping run across the powdery lawn. Their dark forms were silhouettes in the quiet snow. Someone’s shoulder jarred my face as he moved to stand between Shinner and me; the cold leather of his jacket was against my eyes and smelled of smoke. The boys themselves smelled dirty, oddly sweet, like urine, and the open flask had spilled on someone’s sleeve. Suddenly the clear cold was full of commotion. The boys surrounded Shinner as though to protect him and began to pull him away; one of them trod heavily on my feet and left the print of his boot on my canvas shoes. Excluded by the jostling of their big bodies, I understood they were saving Shinner, not me. “I’m sorry,” I said to no one. Shinner didn’t look back and the boys led him quickly toward the truck; one of them waved me away good-naturedly.

As they moved off into the snow, a blur of arms and broad backs, I saw my father’s big Pontiac turn into the half-moon drive of the school. The car slid as he braked too sharply and slowed to a stop. Across a small sea of weather and darkness, the white car sat like a gleaming boat, headlights throwing their long beams into the slant of the snow. The snow was turning to rain. My father put the car in parking gear as he opened the door and the interior light clicked on. Inside this small, lit room I saw the familiar movement of his shoulders, his gloved hands. He pushed the heavy door of the car quickly open, and half stood in the drive, one hand still on the wheel. His questioning face was in shadow, lit from below by the dim yellowed light of the car.

I raised my hand to tell him everything was all right, to wait while I went inside for my coat, but he misunderstood and walked over toward me. His boot buckles jangled with every footfall and the abandoned Pontiac buzzed, the keys still in the ignition.

“What the hell is going on here?” my father asked when he reached me.

“Nothing. I came out for some air and he was here, talking to himself.”

“Who was here? Who was that?” Mitch looked after them into the parking lot.

“Mr. Black, Kato’s father.”

“You mean Shinner Black?” My father shook his head, half in sympathy. “Christ,” he said.

A gust of wind peppered us with sharp snowy rain and my father pulled his hat down over his eyes. I was trembling but I wasn’t cold. A slow warmth had eased through me.

“What are you doing in the cold with nothing on?” Mitch said. “Go get your coat. I’ll wait right here in the car.”

He hunched his shoulders and moved back into the rain as I turned and felt for the cold knob of the heavy door. It pushed open easily, as though pulled from within by the crowded warmth and bright fluorescence of the gymnasium. I could hear cheers; the girls were beginning candling maneuvers and the loudspeaker system crackled air. The lights went dim. I got my coat from my locker and watched by the gym door. They stood in formation, the candles two hundred lights in the dark, and stereo speakers released the melody: “Blue moon, I saw you standing alone.” Flames circled and dipped as the spotlight lit the crescent we’d cut from a sheet and stretched across a wood frame. The silver foil clouds moved on dependable wires, gliding slowly across the face of the moon.

Monday morning I stood on the corner near our house, waiting for the school bus. In my pocket I had a letter to Kato from Billy—Shinner would send it to her. I didn’t want to go to school, and the pool hall would be empty now. Abruptly, I turned and walked down the hill into town. It was a bright winter morning, snow thawing to slush. I could hear gutter water flowing in the street drains, a sound loud and close up and fresh. The air felt like early spring, as though everything had emptied, lightened and warmed, because Billy and Kato were gone.

Before I got to the pool hall, I could see Shinner’s truck parked in front. Evidence of his presence gave me pause, but I kept walking. If my nerve failed I could just pass by, walk past the movie theater onto Main Street. But I crossed, touched the chrome bumper of the Chevy truck, and walked up the steps of the hall. Through the storefront window I saw Shinner at the bar, smoking and looking at notebooks. His expression was serious and he looked the picture of normalcy: a man at work. If I’d found him in the same state in which he’d appeared to me the night of the storm, a kind of apparition that canceled everything else, I’d have felt more confident. I knocked on the steel door and heard him walk over. The door opened.

“I’m Billy’s sister,” I said, as though he wouldn’t remember.

He stepped back to let me enter. “Billy get off OK?”

“Yes. Yesterday morning.” I followed him across the big room to the bar. The hall was empty, the tables covered with plastic cloths. The notebooks were

account ledgers, full of figures. Beside them sat an ashtray full of butts and a Styrofoam cup of coffee.

“Want some coffee?” He moved behind the bar to pour it before I could answer, then set a steaming cup in front of me. “I don’t have any milk, just these things.” He pushed forward a basket of creams packaged in individual plastic cups. “Half-and-half, pretty fancy.”

“I have something for Kato,” I said quickly. “A letter from Billy. He said you would send it to her.”

He shook his head. “Not yet. You keep it. In a week or so, I’ll call and give you the address.”

I nodded. We sat awkwardly, looking at the cup and its dark liquid.

“I’m sorry about the other night,” he said quietly. “I’m sorry if I scared you.”

“That’s OK.” I turned to face him. He sat, just watching me, in his dark green flannel shirt with the cigarette pack in the pocket. His forearms were muscular. His features were strong and regular but he looked almost as old as my father, handsome and ruined. His pants were a little too short and he wore white athletic socks and sneakers. I saw every detail of him, the way he looked.

“I sent Kato to my sister,” he said. “It’s good they’re apart. She did it to keep Billy from leaving, but if he’d stayed, what would that tell her?”

I wasn’t sure, so I didn’t answer.

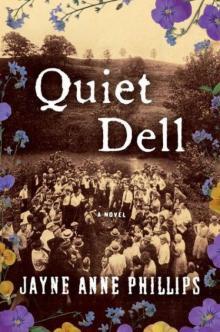

Quiet Dell: A Novel

Quiet Dell: A Novel Lark and Termite

Lark and Termite Machine Dreams

Machine Dreams Fast Lanes

Fast Lanes Black Tickets

Black Tickets