- Home

- Jayne Anne Phillips

Lark and Termite Page 2

Lark and Termite Read online

Page 2

“One minute test,” Tompkins had repeated in Korean, “where are the fucking ROK?” Taejon had fallen. Eighty thousand Republic of Korea soldiers had simply taken off their uniforms and disappeared, dressed in white, and joined the southward flow of refugees. Numerous American kids would have done the same if white clothes had offered any protection. Instead they fled while they could walk, leaving M1s and Browning automatics too heavy to carry. “Babies,” Tompkins said. “White man’s gotta have guns. Now command will hump them back here to pick up their goddamn rifles, and whoever isn’t dead will get his ass creamed.”

Just off the transport ship from the States, Leavitt had signed on to play swing at the Officers’ Club in Tokyo. Dance music and standards, home away from home. The place was a cement-block rectangle called the Match Box, fitted out with ceiling fans and a central raised platform for the band. That first night, he and Tompkins replaced musicians who’d finished their rotations and shipped out. Tompkins was a drummer; he liked telling everyone straight off he was Seminole and did any jack man want to discuss it. He was a big guy with a hawklike nose, a nose that could pass for Jewish without the wide jaw, the heavy-lidded, nearly black eyes, the high, broad bones of the face. Leavitt misheard his name; at the end of the first set, he asked why the hell Tompkins’ mother named him Irving if he was Seminole. “My mother was Semi-nole,” Tompkins said, “and my father was a big dumb cracker named Ervin. That’s Spec. 4 Ervin Tompkins, Belle Glade, Florida: inland, near Lake Okeechobee. Plenty of Seminoles with cracker names. What about you, Philly boy, your old man named Irving? He like his boy playing jazz?”

“His name is Meyer,” Leavitt said, “and no, I’ve not seen him lately.”

“That so,” Tompkins answered. “Sounds like you might have scratched up a living here and there with that horn. You twenty-two, twenty-three? You got four or five years on most of these boys.” Tompkins was nearly thirty, an old man; he’d missed World War II serving time in Kissimmee. Involuntary manslaughter, first offense. By the time he got out the musicians he’d played with in West Palm and Boca had died in Europe or moved on. The recruiter didn’t seem to mind that Tompkins had gone to jail for hitting a drunken adversary too hard. Tompkins figured the peace- time army was a better meal ticket than digging ditches, and here he was, in an Occupation force of uniformed kids. “You and me are senior partners,” he said. “Most of these boys are so snot-nosed and soft nobody’d take their money in Hialeah.”

Florida, to hear Tompkins tell it, was full of towns that might have been named for women: Hialeah, Sanibel, Kissimmee, Belle Glade. Storybook names for storybook places. Korea was no storybook. After Chonan, he and Tompkins traveled by night and hid by day when the NKPA moved. They found the swarm of the retreat east of Taejon and were told to wait a day for replacements. What’s left of the 24th moves now in broad daylight, visible as fleas on a pup’s belly, flanks exposed, easy to surround on flat, low land. They’re setting up perimeters in a sea of moving refugees, with nothing but bazookas and 4.2 mortars to lob against Chinese tanks.

MacDowell is dead, shot in the chest at the fall of Seoul, but the ROK 6th Division he advised had defended the approach to Chunchon through numerous guerrilla incursions. The 6th was combat ready and held for three days, until adjoining units on both flanks collapsed and fled, leaving them no choice but retreat. Leavitt supposes most commanding officers actually fighting this disastrous string of first stands are dead; who knew if MacDowell had prolonged their lives or doomed them by inventing Language Immersion Seoul? GHQ would have shipped the 24th over within days of the invasion anyway. Leavitt and Tompkins would have landed in Korea as disoriented, stupidly arrogant and panicked as all the rest.

Instead, relative veterans, they move in a hard scare more like anger than fear. Not so stupid. The first months with LIS were an extension of the illusion in which KMAG functioned: the illusion there was time. Time for a first group of sixty enlisted men to learn phonetic Korean while they “assisted agricultural projects;" time to minimally increase forces without alarming politicians happily demobilizing a successful American military that, after all, deserved a resumption of civilian life. Language Immersion Seoul only deepened Leavitt’s belief in language and sound as the only tincture of reality, particularly in this place; all else in Korea seemed hallucination, the immense unraveling of a completely foreign history. Six ROK instructors drilled LIS six hours a day, six days a week, ten men to a classroom; mimeographed texts on Korean customs and history, tape recorders, timed recitations of romanized Hangul phrase and response. Daily minute tests were evaluated for tonal accuracy. They were granted weekend leave based on twice-a-session minute test scores; the tests now seemed particularly asinine and yet vitally important. The slight, finely built ROK instructors were polite and consenting except during drills and tests, when they betrayed an urgency and frustration that were infectious. Leavitt heard the hatred and distrust, the discomfort, the resentment in their voices, as warning and knowledge. They were angry and their country was defenseless; everyone would pay. Meaning didn’t matter; the real content of the words was in sound itself. Leavitt punched out answering phrases in sliding nasal tones that were precise and nonverbal as musical scales. At night he decoded innocuous phrases about spicy food or the conversion of miles to kilometers, aware KMAG knew nothing. Or KMAG knew and could do nothing. They were minding a volcano. The ROK instructors stood poised like bantams, shouting. Igot chungeso issuseyo? Which of the following items do you have? They communicated an instinctive, coiled tension Leavitt now recognized as fear.

Officially the newly imported enlisted men were support staff; afternoons they filed orders and requisitions, made supply runs for the mess. Leavitt and Tompkins were partnered in their own so-called agricultural project; they drove a supply truck to the docks for fish, vegetables, freshly slaughtered meat, maekju beer, and rice vodka called soju that could take your head off. Tompkins was happy in Seoul. He used supply runs to scope out clubs, bars, brothels; he liked the native food, sushi and barbecued kalbi ccim, pungent ccigae stew. This food is healthy, he’d tell Leavitt. You seen any fat Koreans? You notice how they turn seventy before their skin wrinkles? You’re no Korean, Leavitt told him, no matter how much kimchi you eat. But Tompkins insisted they drink ssanghwa tea in the barracks at night; he maintained the bitter herbs extended concentration. Their scores on minute tests were always highest; nights they were confined to quarters, they practiced scatting Korean phrases just as they’d improvised swing at the Match Box. In Tokyo they’d watched officers jitterbug with their perfectly coiffed Japanese dates. The women were child-sized girls in upswept hairdos and sheath-style kimonos. They side-fastened their dresses right up to their chins with a hundred hooks and eyes: a married officer on extended rotation might buy them a little house or apartment near the base. Tompkins scoffed at them: “Fuck the white man and the white man fuck you.”

“Like you’re not white,” Leavitt remarked.

“White like you white, Philly Jew boy. No Florida cracker tell you I’m white, or you neither. We knew how to fight before we joined any army.” Tompkins smiled. “These good ole boys got their asses on another powder keg in Korea.”

“Yeah, well your Seminole ass is here as well.”

“Ain’t that the way,” Tompkins said softly. “I need me a hell of a whaling.”

Those weeks in Seoul before the war, Tompkins liked to pretend the Korean whores fucked him instead of the other way around. Every day around four or five, he’d say, “I feel like getting out. Wanna talk about it?”

Leavitt would repeat his stock response: “We can talk about it.”

“You sweet bohunk,” Tompkins would say. “What the hell, no Jew has hair like that.” He’d grab Leavitt’s tight blond curls and hold on.

The papa-san at the place Tompkins frequented always looked delighted to greet them. “Chon bui, chon bui, ” he’d grin, payment in advance, no matter how stridently Tompkins insisted the girls ssage ha

ejuseyo, make it cheaper. “You big minam Americans,” he would tell them, gesturing with an extended forefinger, “you number one men.”

Tompkins always demanded a full hour. Leavitt would follow him up the stairs and take the adjoining room. The walls were, literally, paper: floor-to-ceiling screens that turned one room into two cell-like cubicles, each with a bed, a sink, a chair, a kerosene lamp on a table. Shadows, seemingly those of a giant and his children, moved across the walls as Tompkins stood or turned or lay down, lifting one partner and then another an arm’s length above him as though she were a pet or a baby. Leavitt closed his eyes, allowed an angel to kneel before him. He wouldn’t put himself inside them: he adhered to this small fidelity like religion, like another charm, enjoying the control itself, the tension and the heat. The women laughed at him and blew him kisses, poised themselves naked over him to tempt him. It didn’t matter which woman, which girl. In Korean, he’d tell her what to do, how to dance, moist in the little room, not dancing as she did in the bars but as she had in her village, slow ceremonial dance that was ritual and folklore. They’d all come from a village, years back or not so long ago, all the women and the girls. A girl who’d grown up in Seoul might protest she didn’t know those dances, but he’d keep asking, say he knew her mother had taught her, back when she had a mother. She’d dance then, as they all did, slowly, a prayer beyond language, a shape moving in afternoon light or near darkness. The swanlike turn of the arms, the flex of the arched feet, were always the same. She would arch her back as the last sequence of movements ended, her torso very still. Sometimes she would cry and Leavitt would ask her to lie down, open toward him in his chair, touch herself until the crying stopped or turned to sighs and whispered gasps. The only sex they responded to was with themselves, and they seemed to think him so strange or non-threatening they occasionally forgot he was there, or perhaps shared their privacy as a gift. Regardless, when the performance seemed genuine enough and time was nearly gone, he’d stop the girl and pull her to him, so aroused he was shaking. Finally she’d minister to him with her mouth, both of them listening as Tompkins rammed himself again and again into the youngest, most petite girl he could find. Tompkins called her his lucky star. Leav-itt could hear him call out, nearly crying with adoration, begging her, stroking and praising her. Tompkins paid his favorite girl and her pals with sonmul and tambae, gifts and cigarettes, separate from the papa-san, and by the second week the two or three youngest would be waiting. Some nights they all went with Tompkins; they seemed to demand this of the papa-san as their due if business was slow.

Afterward, Tompkins would say he felt guilty, but the older ones gave you the clap. “Tight and light is right,” he’d say.

Tompkins is right about something; he’s still alive and not a scratch on him. Leavitt is unscathed as well; they’re fucking charmed, Tompkins says, voodoo san, but it was Tompkins’ voodoo. Leavitt feels a bruised apprehension deep in his gut, like it’s only a matter of time before a soft core inside him betrays the hard, fast reflexes he’s honed to a pitch. Tompkins plays war like it’s filthy sport. I’m not really here, he liked to whisper, but MacDowell had picked them both, let them in on secrets that detonated.

Leavitt supposes MacDowell’s idea wasn’t wrong. If KMAG had imported thousands of infantry two years ago, enrolled all of them in MacDowell’s LIS program instead of the sixty they’d imported through Tokyo GHQ, the NKPA might not have poured in so fast, driven their unresisted tank convoys down the one paved road. The Imperial Road, Koreans called it, the old royal highway from Pyongyang to Seoul, but it was peacetime and the road was empty. GHQ allowed Colonel MacDowell his little hobby. Now Leavitt wonders how many LIS guys aren’t dead or captured. The few left are all the more alien for their use of a borrowed language understood in scraps. Rumors are passed on and revised in languages secret from one another. Nearly secret. Leavitt understands a portion of what he hears until he stops listening, concentrates instead on getting the Koreans to a secure location.

Days of drenching rain have given way to ascendant heat; the mud fairly steams, sucking whatever touches it. American troops and matériel struggle north to the front as the front moves relentlessly south. The NKPA are pressing hard; an electricity of threat swells the damp humidity. Leavitt and Tompkins command two stretched-thin platoons assigned refugee management. They’re to assist and direct evacuation of villages in the way of the war, keep the road clear of ox carts and fleeing farmers, but their more important objective is to rendezvous with their own company by nightfall, set up defensive positions, protect the retreat. Their recently arrived force is strung out along a moving human border; boys accustomed to soft Occupation life are dying merely to engage and retreat. Leavitt can only keep them moving, reined in where he can see them.

A streambed and culvert along the opposite side of the railroad tracks run with trickling water; the Koreans seem to think it’s drinkable water, but Leavitt calls to them not to pause. Gaesok kaseyo! Keep going. Sounds of artillery fire drift closer as he squints into the tracks. The land deepens; ahead the tracks pass levelly across broad, matching concrete bridges; identical tunnels under the bridges span a stream and a dirt road. He’ll halt the column there, let them drink and rest in the cool of the tunnels, radio command. Tompkins has the radio. Typically they stay in sight of one another, but the new troops are so raw that Leavitt walks point and Tompkins brings up the rear, mom-and-pop style, in case they’re fired upon. The refugees move forward in near silence; they walk steadily along the tracks through muddy, saturated land. Far off the foothills steepen, forested and green, against a broad horizon so impenetrable it looks painted against the sky. The land is oppressive, ancient, dominant, cultivated in small patches, borrowed for scant lifetimes of subsistence farming. Lifetimes on the move now, blinks of an eye. Whole villages emptied out, moving, frightened populations, imported armies— none of it matters. Generations of political animosity and serial foreign occupation are passing weather, and the hulking mountains watch. NKPA controls those mountains, that sky. Leavitt warned his men at dawn to stay close, stay tight. Now he pulls in the straggling platoon with shrill, aptly timed whistles, accompanied in his head by Lola’s words, private sounds soft with darkness. Baby? You tired? Come here, baby. He’s past tired. There’s no tired, just a tight-strung, alert exhaustion fueled by watchful fear and barely controlled rage. Pressed and pressed, falling back in panicked or slow retreat, they’re outnumbered and little supported, fingers in the fucking dike. Fear and anger turn in his gut like a yin-yang eel, slippery and fishlike but dimly human in its blunt, circular probing, turning and turning, no rest. This alone, the exhaustion, and the mud, the heat—he shares with the Koreans on the tracks. Changma rains have pounded Korea the past two weeks. The runny mud has solidified to warm, pliable clay, and rumor has it tanks are circling in behind them. Infiltrators in peasant white have repeatedly moved behind American troops by joining crowds of refugees. No way to know.

Leavitt’s shrill, pursed-lipped signals (here’s a kiss for you babe) pierce the dull slip-timed sound of movement across the wooden ties of the railroad tracks. Easier than struggling through mud, but the necessity of measuring each step proves too much for the old people, some of the women struggling with infants and bundles. They’ve fallen out onto the gravel between the two lines of track, straggling on at a slower pace. Leavitt lets them; he can’t afford men to police both sides of the column, can’t guard against infiltrators on both flanks if in fact they exist. He wants all his men where he can see them in case of snipers or attack; he fears the new replacements are so green they’ll fire on one another if they’re spooked. He calls to the Koreans rhythmically, consistently, on the beat, partly to calm his own men: Ppalli. Hurry. Kapshida. Let’s go. The refugees need no urging; it’s their civil war, their homes and lands lost, he’s merely a conductor. No savior here. The saving will come later, American command assures Leavitt, Tompkins, all the men who’ve survived the past month to lead boys bare

ly out of basic. Leavitt’s hoarsely tonal shouts of Ttokparo! Ijjokuro! serve as adjacent percussion to other pictures he remembers intensely, starkly, across a terrible gulf of time and dimension. In another world, on an American morning lost to him, Lola whispers phrases on clean sheets in their room above the club. My beautiful blond Jew, my Pennsylvania boy. She loved to tuck her forearms under him as though he were her child and hold his sex to her mouth, drinking him in, her lips and tongue everywhere. Teasing him with her teeth, biting a little, then harder. He uses her words that were sex and song a year ago to keep his feet moving, keep him tensed and angry enough to stay alive and ride his boys like the ruthless fast-promoted cannon fodder he’s become.

This failing police action is UN in name only. The Americans, caught completely off guard when the North invaded in June, are scrambling, their asses hung out to dry. Ironically, the three months in Seoul with LIS before the invasion have made Leavitt one of the 24th’s more acclimated platoon leaders. Language Immersion Seoul was a pilot program MacDowell had hoped to expand. Regardless of any affiliation with Intelligence, MacDowell told them, more military capable of “social interaction” would be useful as tensions seesawed and North Korea continued its Red Chinese–inspired posturing. That was probably bunk. As far as Leavitt could tell, there had never been American Intelligence in Korea. Intelligence stayed dry, ate better, dressed in street clothes, and failed.

Clearly, some of those involved in LIS were being considered, quietly interviewed. That first day in Seoul, they’d had a file on the desk: Leavitt’s high school transcript, the citywide Latin prize he’d won, the community college scholarship he’d turned down to spite his old man, records from Fort Knox. They’d made inquiries.

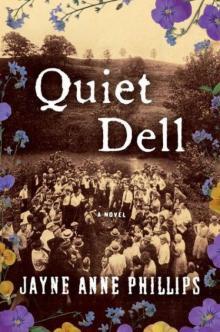

Quiet Dell: A Novel

Quiet Dell: A Novel Lark and Termite

Lark and Termite Machine Dreams

Machine Dreams Fast Lanes

Fast Lanes Black Tickets

Black Tickets