- Home

- Jayne Anne Phillips

Lark and Termite Page 5

Lark and Termite Read online

Page 5

Now I feel how all my collections are just sitting there. They’re things I used to want, and I can’t tell why I did.

I pull the stopper in the sink. The water circles the drain in a soapy funnel I wish I could stand inside, everything pulled round me, pulling tighter and tighter. That’s how it feels when someone stares. People stare at you like you’re food on a plate, and you can feel the power of how bad they want something. They stare at me one way, keep staring, but they stare at Termite and look away. Termite never stares. That’s because he can’t, Nonie would say, no mystery there. It’s true his eyes move because his muscles are quiet and don’t work, but I think he knows he can’t want things, not hard, so hard, the way people do. He does things another way. He doesn’t do anything, Nonie would say. I don’t believe her.

He hurts her more than he hurts me. That’s why she says what she does.

I wash out the sink and rinse my hands. It’s time to get Termite. That alley cat is sitting in front of his chair again, watching the plastic move. That cat scares me. Really it just sits there, looking at him with its yellow eyes, and sometimes it gets down in a crouch. I see that cat at the rail yard when I take Termite to see the trains. I’ve seen it for years. The stray cats slink around by themselves and they’re always alone. Low to the ground, afraid of the dog packs probably. I tell Termite the cats eat the rats and the dogs eat the cats, just like “Three Blind Mice.” Then he’ll do the first lines of the rhyme in sounds and I’ll have trouble getting him to stop. He remembers cadences of songs and rhymes, like he recognizes sounds, not words. He doesn’t need words. He needs his strip of blue, and the space under the rail bridge by the river. He needs to see the river while the train roars over top. He needs the rail yard.

He loves going there in the wagon when the sun glints on the rails. The tracks go off in every direction and the trains screech and hoot and begin to move, so slow we can keep pace just beside them. That close, the noise takes over, shakes in the ground. Termite sits up straighter and gets real still. He likes vibrations so big they get inside him. He’s so pure he’s filled up more than I could ever be, more than I am, running and pulling the wagon. Afterward, when I’m out of breath, on my knees and leaning back against the gritty wheels, I feel drenched, soaked, washed away, and the train is still blaring in a fade that streaks away from us, a fierce line hanging on. The yard is two blocks west so we hear the freight trains every morning, sounding at the crossing, and Termite makes sure I know how wrong it is he can’t get what he wants. He doesn’t say anything, only uses his elbows to sit up a little straighter and turn toward the sound, tilts his head, his ear like an open cup. There: the 6:52. I crank the window open a little wider to hear the fast bellow, the hush and hollow of it. Even from far away, it makes a quiet in the air it rips. It pours through. I’ll give him a moment. I’ll give him one more moment.

Nonie hates the idea of blue cake, she says it looks like something old and spoiled, too old to eat, though it’s light and delicate and flavored with anise. But Termite likes it, and he likes pink cake that tastes of almond, and mostly he likes me putting the batter in different bowls, holding them in the crook of his arm while I bend over him, stirring. I tell him how fast a few drops of color land dense as tinted black and turn the mix pastel. I make three thin layers, pale blue and pink and yellow, and I put three pans in to bake, shut the door of the oven fast to pretend I’m not making everything still hotter.

“Hot as Hades today,” I tell Termite, and I move his chair so he gets the hint of breath from the window. The radio cord still reaches and he turns the knob with his wrist, slow or fast, like a safecracker, like there’s some sense to the sounds, the static and the interrupted news.

“Don’t try talking to me in radio,” I tell him, but he does anyway. As long as he holds it, he’ll be trying to make it talk. I take the radio out of his lap and put it back on the counter, and I hold a bowl of icing down low. I hold the little bottle of blue in Termite’s hand, and we let just three drops fall. Divinity icing makes peaks and gets a sweet crust like meringue. Mine is like sugared air that disappears in your mouth. Nonie says I’m a fabulous cook. I could cook for a living, she says, but not at Charlie’s, or anywhere like it. The egg whites can go bad fast in hot weather but I turn up the fridge to keep the icing cool on the lowest shelf. We’ll eat the cake today, this birthday, and Nick Tucci will take some home to his kids. Nobody makes those boys cakes. Rat boys, Nonie calls Nick’s kids, like she’s disappointed in them. Delinquents like cake too, I tell her. You be sure cake is all you’re making them, Nonie says. Then she’ll say she wasn’t born yesterday, like anyone ever bothers me. I tell her no one does. They only look.

It’s true. It’s like I’ve got a beam out my eyes that backs people off. Now that I’m older, I’ve got a clear space around me I didn’t have before. I wonder if that’s like a future, or a place where a future will be.

Pale blue divinity sounds like a dress or a planet. Blue icing does look strange, like Martian food, unless I trim it, save out some white for a lattice over the top, or garlands or flowers. A decorated cake looks like a toy, and people do want it. I’m putting the icings away to keep them cold and I’ve got my whole face in the fridge, near the steaming icebox at the top. The sweat across my upper lip dries in a sudden tingle and then I hear someone at the door. The bell rings in a way I can tell is new.

Good thing or bad thing, I think.

Termite gets quiet.

“Who can thatbe,” I say out loud, like a charm. Like we’re in a TV show about a charming mother and her kid. We don’t have a TV. Termite doesn’t like those sounds. Back then, all those summers, Joey always had the TV on at the Tuccis’, and Termite wouldn’t even go inside. He liked to be moving, or by the river, under the cool of the bridge. There are two bridges, opposite sides of town, both spanning the river; the spiny one for cars, all metal ribs and rattles, and the stone one for trains, wide enough for four lines of track. Once they used all the tracks, Nonie says. Now only two are kept repaired, but two arches of the railroad bridge stand up in the river just as wide, and two more angle onto the land. The tunnel below is still as long and shady and deep. There used to be a road inside but now the road is broken, smashed to dirt and weeds and moss. It’s cool in summer, and the tracks run overhead on their uphill slope to the rail yard. Termite likes the tunnel best. The echoes.

The doorbell rings again, twice. Somebody won’t give up.

I push Termite’s chair out past the dinette into the living room. I leave him sitting by the piano and look through the window in the front door. I see somebody. Brown suit coat and trousers, in this heat. Tie and button-down shirt. Glasses. I open the door and there’s a man standing there with his briefcase in his arms, like he’s about to hand it over to me. Not an old man. Thick lenses in the glasses, so his eyes look magnified. Owl eyes. White blond hair parted to the side under his hat. Fedora, like a banker’s.

“Hello there,” he says. “Hope it’s not too early to stop by. I was hoping I could speak to—” He looks down at the papers he’s got on top of the briefcase.

“My mother’s not here,” I say.

“—your aunt. It says here your aunt. You must be Lark.”

“You’re from Social Services,” I say.

He nods. “Actually I live two streets over, moved in a week ago. I was on my way to work, so I thought I’d stop.” He smiles in a nervous way.

“I didn’t think Social Services was open on Sundays.”

He looks blank for a minute. “Oh,” he says. “Well. I’m new, so there’s a lot to catch up on. I come and go. That’s a good thing about these small towns. It’s more informal. And you can walk to work. Anyway, I can. I suppose you can walk to the high school.”

“I’m not at the high school. I take a secretarial course.” I’ve got my hand on the door and I push it shut just a little.

He steps up closer and looks over my shoulder at Termite in his chair. “This is your brot

her? Termite. A nickname, I’d guess. What’s his real name?”

“Terence,” I lie. I always seem to start lying to these people real quick. Even if I don’t have to.

“By the way, my name is Robert Stamble.” He sticks his hand out at me from under the briefcase.

Stumble, Stamble, I think. And from that time on he’s stumble, stammer, tumble, someone tripping in my head. Right away, I think he’d better leave. He thinks he means well and he doesn’t know anything. I can smell it on him like a hint, like the Old Spice smell of his aftershave. I hate that smell. Dads wear it in Dadville. I look at him closer and see that he doesn’t even look old enough to be much of a dad. He’s pale pink as the rims of a rabbit’s eyes, and blue eyed behind his thick glasses. Hiding in his suit.

“Nonie’s not here,” I say, “and she says the check we get from Social Services is not enough to be harangued or bothered about. If you want to make a home visit, you should arrange it with her.”

“You know,” he says, “we’re very much in favor of in-home care whenever possible, and we want to support you. There may be ways we can help. Physical therapy. Equipment. A wheelchair.”

“I do physical therapy with him,” I say, “a nurse at the clinic taught me. And he’s got a wheelchair, a big heavy one. We keep it in the closet. He doesn’t like it, but we use it for his medical appointments.”

Stamble fumbles around, opens the briefcase, shuffles papers. “Oh, yes.”

“It’s one of the chairs Alderson passed on to the county,” I tell him.

Alderson is the state hospital that closed two years ago, one town over. They shipped the craziest loonies somewhere else and let go the ones that were only taking up space.

“Of course.” Stamble looks up at me.

“Social Services sent it when they said he had to go to the special school.”

Stamble keeps on. “Still, don’t you find it easier than—”

I get it. He’s seen me pull Termite in the wagon. I do most every day. The wagon is deep and safe, with high wooden slats for sides, and long enough I can stretch Termite’s legs out. It’s like the old wagons they used to haul ice or coal. It was in the basement of this house when Nonie moved in. She says it’s probably older than she is. “Termite doesn’t like the wheelchair,” I repeat.

Stamble nods. “He’s a child. He should have a smaller chair, one his size. Something portable would be easier for you.”

“Portable?” I think about that. Coming into port, like on a boat. Termite, bobbing on the waves. I’m watching him through a round window small as a plate. A porthole. We’re coming up on a pretty little town by the sea, and Stamble blink, blink, blinks. For a minute I think he’s fooling with me, or maybe he’s nervous. Where did they get him?

He goes on at me. “Child-sized. Not as heavy. Some of them fold. Easier to take in and out of an automobile, whatever.”

“We don’t have an automobile,” I tell Stamble. I step back. “Anyway, he doesn’t like the chair he already has.”

“Maybe he needs a chance to get used to it, gradually of course. Does he mind the medical appointments?”

“No, not really. I wouldn’t say he minds.”

“Because if he associates a wheelchair only with something he doesn’t like, you might change that by taking him to do something he does like—in the wheelchair.”

I shift my weight and stand so he can’t see behind me. Termite stays real quiet. If he knows when to be quiet, I don’t know how they can say he doesn’t know anything. “Maybe so,” I tell Stamble. “I’ve got to go now. I’ve got a cake baking.” I’m easing the door closed.

“Hot day for baking,” he says. “Someone’s birthday?”

I nod and smile through the narrow space that’s left. “You can call Noreen,” I say. “If you want to talk to her.” I shut the door. The knob turns in my hand and I hear the click.

“Very good to meet you,” I hear Stamble say from outside. “Please let me know if you need anything. I’ll see what I can do about a more suitable chair.” Then I hear his footsteps going away.

Termite has his head turned, his ear tilted toward me, and he doesn’t move. I walk across the room to turn his chair back toward the kitchen and then I smell the cake, a sugary, toasted smell with a brown edge. “Oh no,” I say, and move him back just enough to get the oven open, grab the layer pans with the hot pads. The cakes are a little too brown on top, but not bad.

I show him one. “It’s fine,” I tell him, “a tiny bit burnt, not so you’d taste.” You’d taste, Termite says, you’d taste.

“Don’t you worry,” I tell him.

Nonie

The Social Services people marched right into my living room, their hearts all righteous. He was three or four. Evaluation, they said, services. Maybe an operation so he can get out of that chair. That’s an idea, I said. Then he can scuttle himself out to the street to get hit, or down to the rail yard to fall and cut himself up, or eat that poison they set out for the dog packs. Is that what I need to worry about? They going to give me somebody to watch him every minute? No. They going to take him down to the rail yard to see those trains he spends the day listening for? They going to keep him from walking straight into one? They going to keep those sandlot kids from chucking rocks at him if they find him out by himself? They going to explain to him why those kids are so mean, why they’d treat him worse than an animal? No. The doctors in Cleveland said no promises. That part I believed. An exploratory, they said, see the extent of the damage. Then they did tests, advised against “further trauma,” told me to take him home. Minimally hydrocephalic, they said, and visually impaired. No telling what he would ever know or understand. And his spine hadn’t closed right; he would never walk. The social worker was sorry. She said we could sign up for ADC support, though it wasn’t much, or find an institution to take him if I couldn’t manage. Aid to Dependent Children—what aid? There he sat in his chair the whole time she was talking, his pillows bigger than he was, straining to hold his head up. Eyes hard to the side, looking and looking like he does.

Lark will start in about how he doesn’t like the special school, he doesn’t like the bus, he wants to be here. Maybe you’d like me to quit my job, I tell her, so I can watch over him every minute.

Then so we’re not out in the street over the mortgage and your school fees, maybe you’d like to take my place at Charlie’s. Just go ahead and quit Barker’s two years before you get your diploma, quit and bring in the money we’ve got to have. You for sure could do it as well as me with these ugly feet of mine, and we’d be in fine shape then. I try to tell her: Who takes care of him when I’m gone if you’ve got nothing but Charlie’s?

She’s got no way to better anything but get that diploma and a good secretarial job, same as I told her from years ago. That boy doesn’t know where he is, but he sure would wonder if he was down in the rail yard getting beat with a stick, same as they beat those stray dogs they find out away from the pack. He’s been happy enough in that chair ever since I put him there and he’s not got any pain in those legs. I’m thankful the doctors let him alone. What would he think in a hospital with them doing things and making him hurt, when he’s hardly been out of this house except to the river or up and down Main Street in the wagon? Who says he wants to walk around? Who says he’s missing something? What’s so great about walking around on this earth, I wish someone would tell me. Social Services going to fix that, make it someplace a boy like him can walk around?

Charlie can tell when I get to thinking about it. He’s got his back to me, cleaning the grill, but he looks over at me. “You feeling all right, Noreen?”

The air seems hard to breathe, even in the restaurant. The heat presses right up against the big window, and the air conditioner over the door is gasping. “They might be right about that storm coming tomorrow,” I tell him. “My joints are paining me.”

“Supposed to drop by forty degrees, cool off and blow hard. Rain in sheets, two, three days

, starting this evening. They say half the town will flood. If they’re wrong, all that chili I made today will take up a lot of freezer space. Once the rain starts, we’ll have the city rescue workers in here, and the state people if they call them in. Noreen, you want to leave early?”

“Think I will. The river is high. The alley will flood if it’s a major storm. It’s not like I haven’t been through it before.”

“It’s what comes of living over there in the flood plain,” Charlie comments. “Want me to drive you?”

“You’re the only one here. I’ll walk. I feel like a walk, unless Elise feels like a drive. Elise, you on break?”

She nods. “I am, and I’m not going back to that store for a full hour. That idiot girl of mine was late coming in and she owes me.”

Charlie’s in favor. “Fine. Why not bring everyone back here for dinner? I’ll wait table, treat you like prize customers.”

“Not tonight. I’ll take some chili, and what’s left of the buttermilk chicken. Despite your faults, Charlie, you’re not a bad cook. Must be what keeps me around. I’ve got to be going.”

Charlie reaches over, touches the face of the watch he gave me. It’s a strong, delicate watch, just the width of his big forefinger. He moves the band on my wrist, pressing and caressing at once. He took me to a jeweler to have it fitted just right, so it moves but doesn’t slide. “Right, it’s Sunday. You’ll be expecting Nick the gardener, coming by to fix things up. Mows on Sundays, doesn’t he? He takes an interest, does Nick.” Charlie shoots a glance at Elise, trolling for an ally, but Elise looks determinedly out the plate-glass window onto Main Street.

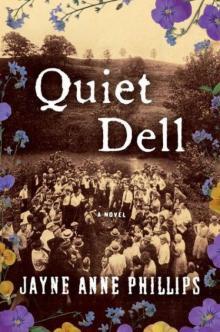

Quiet Dell: A Novel

Quiet Dell: A Novel Lark and Termite

Lark and Termite Machine Dreams

Machine Dreams Fast Lanes

Fast Lanes Black Tickets

Black Tickets